- Home

- About Us

- Sailing Courses

- Powerboat Courses

- SLC - International License

- Yacht Vacations

- Find an On-Water Instructor

- Practical Courses

- Fighting Childhood Cancer

- Free Courses Signup

- Student Benefits

- Gift a Sailing Course

- Sailing Opportunities

- Sailing Licenses and Certifications

- About the Sailing Certifications

- Sailing Blog & Helpful Articles

- NauticEd Podcast Series

- Yacht Charter Resources

- School Signup

- Instructor Signup

- Affiliate Signup

- Boat Sharing Software

- Sailing Industry Services

- Support & Contact

- Newsroom

- Privacy Policy

Marine Diesel Engine Maintenance

MASTER MARINE DIESEL ENGINES

Owning or operating a yacht means knowing your engine will start every time. This online Marine Diesel Course from BoatHowTo gives you the knowledge to maintain, troubleshoot, and repair your diesel engine with confidence. Developed by world-renowned experts Nigel Calder, Dr. Jan C. Athenstädt, and Michael Herrmann, it teaches you the essential skills to keep your engine reliable on every voyage.

✓ Perfect for yacht owners, offshore cruisers, and charter skippers who want self-reliance at sea

✓ Includes clear, step-by-step lessons with video, diagrams, and maintenance checklists

✓ Covers fuel, cooling, lubrication, troubleshooting, winterization, and advanced owner tasks

✓ Lifetime access, including free course updates

✓ Optional certificate of completion available

Essential for anyone investing in their boat, this BoatHowTo course takes the guesswork out of diesel maintenance and gives you confidence where it matters most. Learn at your own pace, online, with permanent access to all materials. Register today!

Estimated Time: 10 hours

Price: $299 Today (NOT included with the Open Ocean Membership)

Bonus: All NauticEd sailing students receive the free Basic Sail Trim and Nav Rules courses, free eLogbook and Boating Resume, and special discounts from our industry partners. What's Included >

What Students Say

✨AI generated from student reviewsStudents report that this course gives them the confidence and know-how to look after their marine diesel engines, often calling it “essential” for any boat owner. Reviewers say the lessons are clear, the right length, and packed with practical detail that helps them prevent expensive failures and keep even 40-plus-year-old boats running better than when they bought them. Many highlight how the teaching brings Nigel Calder’s well-known technical books “to life,” praising his deep expertise across diesel, electrical, and broader mechanical systems. Sailors ranging from world cruisers to newer owners say they’re learning far more than they expected—especially about fuel, cooling, and overall system care—and strongly recommend the course as a must-take for anyone serious about reliable, self-sufficient cruising.

Why Take the Marine Diesel Engine Maintenance Course?

Register for the Marine Diesel Engines online course from BoatHowTo and gain the confidence to handle one of the most critical systems on your yacht. This course distills decades of professional expertise into clear, step-by-step lessons designed for boat owners who want reliability and independence on the water.

Rather than relying on dockside mechanics or hoping for the best, you’ll learn a systematic approach to keeping your diesel running smoothly. The course shows you how to identify problems early, perform the right maintenance at the right time, and make smart decisions about repairs or replacements.

Includes practical planning tools, maintenance checklists, and real-world demonstrations you can apply directly aboard your own vessel.

This Course is perfect for you if...

- You value peace of mind knowing your yacht’s engine is properly cared for

- You plan extended cruising and want to avoid delays and unexpected costs

- You prefer a methodical, professional approach to boat ownership

- You want clear, trusted instruction from recognized authorities in marine systems

Your enrollment includes lifetime course access, regular content updates, addition to your boating resume, and a complete satisfaction guarantee.

Written and Endorsed by Nigel Calder

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN IN THIS MARINE DIESEL COURSE

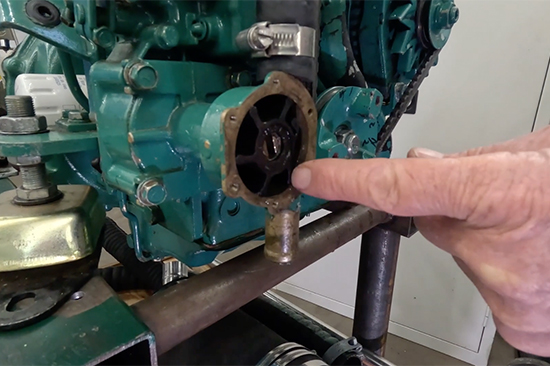

The primary goal is that you enjoy your boating without engine issues. In order to do that, you need to gain the right kind of education to help understand how an engine works, and in doing so, you are able to prevent issues arising. We go through all the core maintenance items that a normal boat owner can perform, but we also identify items that should be left to a professional with the right diagnostic tools. Many of the videos are filmed in the German boatbuilding school, where you are able to observe firsthand how to work on your engine.

View the Course Topics

Understanding Your Engine

- How marine diesels work

- Key components and systems

- Common failure points and how to avoid them

Fuel, Cooling & Lubrication Systems

- Fuel contamination, filtration, and bleeding

- Cooling circuits and impeller changes

- Oil management and service routines

Troubleshooting & Repairs

- Diagnosing smoke, vibration, and overheating

- Electrical and charging issues

- Step-by-step fault-finding methods

Maintenance & Layup

- Routine service schedules and checklists

- Winterization and long-term storage

- Spares and tools every owner should carry

Advanced Owner Tasks

- Valve clearance checks

- Engine alignment basics

- Repower vs. rebuild decisions

- Sea trial methodology and performance curves

Everything You Get with this Course

- Learn how to maintain and troubleshoot marine diesel engines with clarity and confidence.

- Duration: Approximately 8–10 hours, self-paced—learn at your own speed.

- Unlimited Access: Lifetime access lets you review lessons and updates anytime.

- Format: Step-by-step video instruction, diagrams, and downloadable maintenance checklists.

- Certificate: Optional certificate of completion available from BoatHowTo.

- Languages: Offered in English.

- Recognition: Developed by world authorities Nigel Calder, Dr. Jan C. Athenstädt, and Michael Herrmann, trusted by sailors and professionals worldwide.

- Convenient Formats: Access on desktop, laptop, tablet, or mobile.

- Highly Recommended: Essential for yacht owners, long-distance cruisers, and charter skippers seeking reliability and independence.

- Qualification & Endorsement: This course leads to additional qualification and endorsement for boat owner certification.

- Free Stuff: All NauticEd sailing students receive 2 free courses (Basic Sail Trim and Nav Rules), a free eLogbook and Boating Resume, and special discounts from our industry partners.

- View an excerpt from the Marine Diesel Engines Course

Price Today: $299

About NauticEd

NauticEd is the leading provider of modern sailing education, combining online sailing courses with accredited on-water instruction. With over 300,000 students worldwide, NauticEd is the only U.S. sailing body recognized for meeting U.S. Coast Guard and NASBLA standards under the American National Standards for boating education.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS & BOATHOWTO

Boat Electrics 101 was created by BoatHowTo and is led by boating legend Nigel Calder, the most trusted resource for technical boat systems. Nigel's team behind the course brings unmatched authority in marine electrics:

Nigel Calder – Widely regarded as the world’s leading marine technical author, best known for Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual and his decades of work shaping ABYC and ISO standards.

Dr. Jan C. Athenstädt – Marine engineer and educator who has taught electrical systems at universities and boatbuilding schools, specializing in clear, practical instruction for boat owners.

Together, they founded BoatHowTo to provide reliable, standard-based instruction for boat owners who demand more than guesswork or dockside advice. Their mission is simple: make advanced technical knowledge accessible, practical, and safe.

BoatHowTo’s courses are trusted by boat owners, surveyors, schools, and professional installers worldwide. By partnering with NauticEd, this expertise is now available directly in our course directory.

View Marine Diesel Engine Maintenance Course excerpt

List Price: $299.00

Excerpt from the course

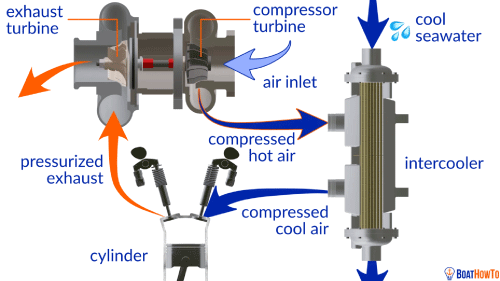

Expand Excerpt from the courseA naturally aspirated (NA) engine is one in which air is drawn into a cylinder by the movement of a piston down the cylinder. This movement lowers the pressure in the cylinder and ‘sucks’ in air. A turbocharged engine has a device that pumps in air, enabling substantially greater amounts of oxygen to be introduced. This allows more fuel to be burned, which increases the power from that engine. This is reflected in an increased power-to-weight ratio, which is often published.

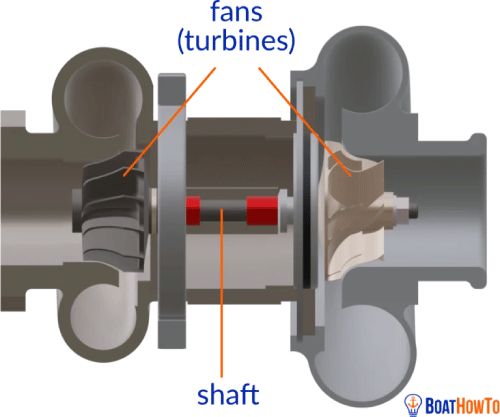

Crudely speaking, a turbocharger has two fans on a common shaft. One fan (the turbine wheel) is set in the path of the exhaust gases as they exit the engine, and the other (the compressor wheel) is in the path of the inlet air. When an engine is running, the exhaust gases, which are moving at a high velocity and still contain a significant amount of unexploited energy, spin the turbine wheel. This spins the compressor wheel, forcing air into and pressurizing the air into the engine’s inlet manifold.

A turbocharger is, in effect, an air compressor driven by the exhaust gasses. Whenever an intake valve opens, this pressurized air is driven into the cylinder as opposed to being drawn in by the piston moving down the cylinder.

At high engine loads and speeds, turbochargers can create excessive inlet (boost) pressure. Many have a wastegate, a device that responds to this high pressure by opening a bypass valve on the exhaust side, reducing the gas flow over the turbine wheel. Turbochargers on many modern engines are considerably more complex, with moveable vanes (variable geometry turbos, or VGT). All can spin at extraordinarily high speeds from 100,000 rpm up to 400,000 rpm in the latest generation devices. Some larger engines have more than one turbocharger with the turbochargers installed in series.

Intercoolers and aftercoolers

When air is pressurized, what happens? The temperature goes up! You might think this is a good thing because we want high temperatures to ignite the diesel fuel, but hot air at a given pressure has less density than cooler air, and less density means less oxygen. For example, air at 50˚C (112˚F) contains 14% less oxygen than air at 7˚C (44˚F). So typically, immediately after a turbocharger, there is a device to cool the air – known as an aftercooler or intercooler (the two terms tend to get used interchangeably, although with the typical single-stage turbocharger, 'aftercooler' is technically more correct, but we have employed the more commonly-used 'intercooler'). This compressed cool air then enters a cylinder where the pressure is raised high enough during the compression stroke for ignition to take place. If you have a turbocharger, you likely (but not necessarily) have an intercooler. Intercoolers require maintenance. We will return to them.

By driving more air into a cylinder of a given size, a turbocharger raises the effective compression ratio. This enables the actual compression ratio - what it would be without the turbocharger - to be lowered to levels that are just adequate for starting. At startup, there is no turbocharger boost pressure, so there is a limit to how low the compression ratio can be. This is generally around 16:1 or 17:1.

Rated Life Expectancy

With or without a turbocharger, given a recreational duty cycle, most of the small marine diesel engines installed in recreational boats have a life expectancy rating before a major overhaul of 5,000 hours. This duty cycle assumes that operation at wide open throttle (WOT) is intermittent. These engines are not rated for continuous duty at WOT.

Instead of hours, the life expectancy before a major overhaul of commercial engines is sometimes rated in the volume or weight of fuel that will be burned. The more power that is extracted from a given engine the faster the fuel will be burned and the less the operating hours before the overhaul.

>>>>>

Nigel and Jan's course has 86 lessons similar to this with handy "how to fix" instructions for each engine component. Get the course now.

Sea talk testimonials

Just finished 7 days bvi bareboating a Lagoon 440 catamaran. Could not have done it, or even tried it, without your excellent training. Thank you for your help.